My Biography, Career, and Work on Gambling Harm in New Zealand

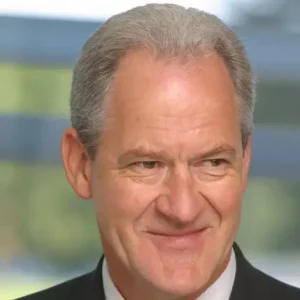

My name is Max Wenden Abbott. I was born on 7 June 1951, and I have spent most of my professional life working as a psychologist, academic, and researcher in the fields of mental health, addiction, and gambling-related harm. Over several decades, my work has focused on understanding how gambling participation and harm develop at both individual and population levels, and on promoting a public health approach to gambling policy in New Zealand and internationally.

My career has not followed a single narrow path. I began in clinical psychology and addiction research, moved into national and international mental health leadership, and later became deeply involved in large-scale gambling research designed to inform public policy, prevention strategies, and public debate. Throughout this journey, my central concern has remained the same: how evidence can be used responsibly to reduce harm and improve wellbeing.

Why My Work in Gambling Research Matters

When I first became involved in gambling research, discussions about gambling harm were often shaped by moral argument, stigma, or anecdote rather than systematic evidence. Together with colleagues and collaborators, I sought to change that.

My research has aimed to answer practical and policy-relevant questions:

- How many people gamble, and how often?

- Who is most at risk, and why?

- Which gambling products are most strongly associated with harm?

- How does harm extend beyond individuals to families, communities, and wider society?

- How do regulation, availability, and commercial practices influence population-level risk?

I have consistently argued that gambling-related harm should not be understood simply as a consequence of poor individual choices. Instead, it is often a predictable outcome of exposure to certain products, environments, and marketing practices—an understanding that aligns with broader public health thinking and underpins much of my later work.

Early Life and Education

I was born in Featherston, in New Zealand’s Wairarapa region, and attended Kuranui College in Greytown. My academic training progressed steadily through psychology, education, and clinical practice.

My formal education includes:

- Victoria University of Wellington — Bachelor of Arts (1971) and Bachelor of Science (1973)

- Christchurch Secondary Teachers’ College — Teaching qualification (1974)

- University of Canterbury — Master of Arts (1977)

- University of Canterbury — Doctor of Philosophy (1979)

- University of Canterbury — Postgraduate Diploma in Clinical Psychology (1980)

My doctoral research examined cognitive factors influencing outcomes among people with chronic alcohol dependence. That work shaped my long-term interest in how cognition, behaviour, and environment interact—an interest that later translated directly into my approach to gambling research.

From Clinical Psychology to Mental Health Leadership

My early professional career was closely connected to New Zealand’s mental health sector. In 1981, I became the founding National Director (CEO) of the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand, a role I held until 1991.

Establishing and leading a national organisation required more than clinical expertise. It involved advocacy, public communication, policy engagement, and collaboration across government and community sectors. This experience strongly influenced my later work: it reinforced my belief that complex social and health problems cannot be addressed in isolation and require systems-level responses.

In the early 1990s, my work expanded internationally. From 1991 to 1993, I served as President of the World Federation for Mental Health, contributing to global discussions on mental health promotion, prevention, and human rights.The AUT Years: Building Capacity for Research and Policy Impact

In 1991, I joined the Auckland Institute of Technology, later known as the Auckland University of Technology (AUT). I served for many years as Dean of the Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences and later held senior executive responsibilities, including the role of Pro Vice-Chancellor.

My time at AUT provided a stable institutional platform for long-term, policy-relevant research. Large national studies require continuity, multidisciplinary teams, funding pathways, and trust between researchers and government agencies. AUT enabled this work, particularly as New Zealand sought robust national evidence on gambling participation and harm.

In 2011, AUT marked my 20 years as Dean, reflecting the scale of my involvement in building academic capacity in health and public policy research.

National Gambling Research and the New Zealand Gaming Survey

A pivotal phase of my research career involved leading major gambling studies commissioned by New Zealand’s Department of Internal Affairs (DIA). I led a research consortium—together with Dr Rachel Volberg—to conduct the New Zealand Gaming Survey.

These national prevalence studies were designed to go beyond simple counts of “problem gamblers.” Their purpose was to map gambling behaviour and harm across the population, identifying:

- demographic and regional participation patterns

- dominant gambling products by frequency and expenditure

- clustering of risk factors (such as high spending or frequent play)

- the broader social and familial impacts of gambling-related harm

Such evidence is essential for informed regulation, public health planning, funding of treatment services, and evaluation of harm-minimisation policies.

“Taking the Pulse” and Long-Term Evidence

One widely cited output from this work is “Taking the Pulse on Gambling and Problem Gambling in New Zealand”, the first phase of the 1999 National Prevalence Survey.

Reports of this kind become benchmarks. They allow later researchers and policymakers to assess trends over time, identify emerging risks, and evaluate whether changes in regulation or market structure are associated with increases or reductions in harm.

My later work, including long-term analyses spanning multiple decades, sought to synthesise these data into coherent narratives about how gambling environments evolve and how harm follows predictable patterns.

Gambling Harm as a Public Health Issue

A central theme of my work has been the argument that gambling harm exists on a continuum. Harm may include financial stress, relationship conflict, emotional distress, reduced wellbeing, and community-level impacts—not only clinically defined problem gambling.

This perspective aligns with public health approaches used to understand other harmful commodities. When products are widely available, intensively marketed, and designed to maximise engagement, population-level harm should be expected—even if only a minority of individuals meet diagnostic thresholds.

My involvement in the Conceptual Framework of Harmful Gambling, including later editions, reflects this systems-oriented view. These frameworks help researchers and policymakers adopt shared definitions and measure harm beyond individual pathology.

Recognition and Honours

My work has been recognised at both national and institutional levels.

Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM)

In 2016, I was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) for services to health, science, and education.

AUT University Medal

In 2018, I received the AUT University Medal, recognising my contribution to academic leadership and public health research.

Controversy and Resignation from AUT

Any comprehensive account of my career must also acknowledge significant public events. In 2020, I resigned from AUT following allegations of sexual harassment and related institutional processes. These matters were reported by multiple media outlets.

I note this here in a factual and neutral manner. Public reporting reflects only part of complex processes, and detailed conclusions depend on investigative, institutional, and legal contexts.Reflections on My Legacy

Looking back, my work has aimed to contribute in three main ways:

- Evidence-based gambling policy — supporting decisions grounded in data rather than assumption

- Broader definitions of harm — recognising impacts on families, communities, and wellbeing

- International integration — connecting New Zealand research with global frameworks and debates

My enduring belief is that research has a responsibility not only to describe problems, but to inform ethical, effective, and compassionate responses.

Workplaces & Roles

Selected Works by Max W. Abbott

Reflections on Research, Policy, and Responsibility

As my work in gambling research developed, I became increasingly aware of the responsibility that comes with producing evidence in a politically and commercially sensitive field. Gambling is not a neutral activity. It exists at the intersection of entertainment, government revenue, corporate interests, and public health. For that reason, research findings rarely remain confined to academic journals—they quickly enter public debate.

One of my central concerns has always been how evidence is interpreted and used. Data can inform policy, but it can also be selectively quoted or misunderstood. I have therefore tried, wherever possible, to communicate research findings clearly and cautiously, emphasising uncertainty where it exists and resisting simplistic conclusions. Gambling harm is complex, and no single statistic captures its full impact.

A recurring challenge in this field is the tension between individual responsibility and structural responsibility. While individual behaviour clearly matters, my research has consistently shown that behaviour is shaped by availability, accessibility, marketing, and product design. From a public health perspective, it is neither accurate nor ethical to place the burden of harm solely on individuals while ignoring the broader system in which gambling occurs.

I have also placed strong emphasis on longitudinal evidence. Short-term studies can be misleading, particularly in environments where gambling products and regulations change rapidly. By examining trends over decades, it becomes possible to identify patterns that are otherwise invisible: delayed harm, cohort effects, and the cumulative impact of exposure over time. This long-view approach has been central to my work in New Zealand.

Another important aspect of my career has been collaboration. Much of my research was conducted in partnership with statisticians, clinicians, sociologists, economists, policymakers, and international colleagues. Gambling harm cannot be understood from a single disciplinary perspective, and I have always believed that multidisciplinary work produces stronger, more credible results.

Finally, I have seen research as inseparable from ethical reflection. Gambling research is not abstract. It concerns people experiencing financial distress, relationship breakdown, mental health challenges, and loss of wellbeing. Maintaining respect for those affected—and avoiding stigmatising narratives—has been a guiding principle throughout my work.

In reflecting on my career, I recognise that evidence alone does not create change. However, without evidence, meaningful and responsible change is impossible. My hope is that the research to which I have contributed continues to support informed decision-making, balanced regulation, and a more honest public conversation about gambling and its harms.